-

電(diàn)話:0755-86522445電(diàn)話:0871-67370722

-

郵箱:yunshuohr@sina.cn

For hundreds of years, scientists have suspected a connection between our personality traits and taste preferences. Anton Brillat-Savarin, the famous French gastronome, is quoted saying, “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you who you are.”

數百年來(lái),科(kē)學家(jiā)們一直懷疑我們的性格特征和口味偏好之間(jiān)存在聯系。法國(guó)著名美食家(jiā)安東·布裡(lǐ)亞-薩瓦蘭曾說過:“告訴我你吃什麽,我就(jiù)能說出你是(shì)誰。”

告訴我你吃什麽,我就(jiù)能告訴你你是(shì)誰。

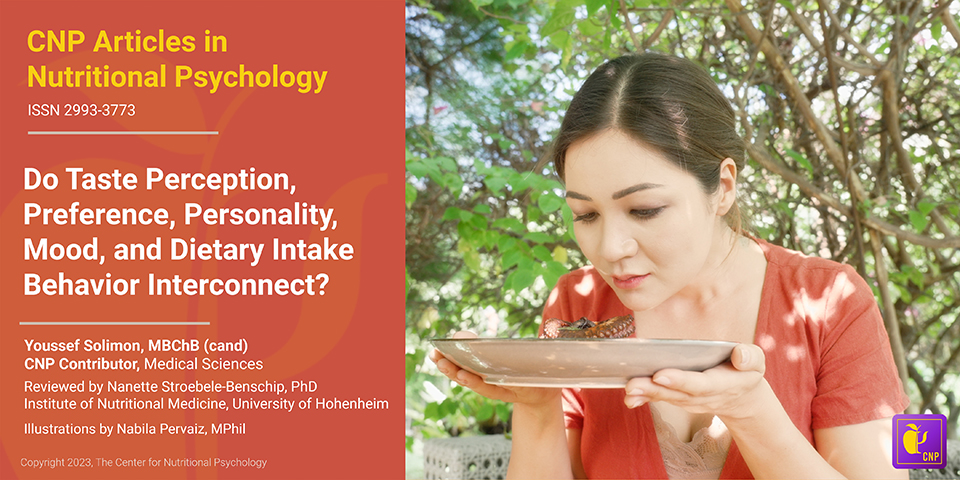

But what influences what we eat? It turns out that a symphony of elements influences our dietary intake patterns. These elements include (but are not limited to) our psychological traits (and mood states), cognitive and perceptual processes, behavioral attributes, psychosocial (including cultural) environment, and interoceptive experience. Each of these elements, in turn, is driven by physiological, biological, neuropsychological, and environmental states that are constantly at play within us (figure 1) (see the Nutritional Psychology Research Library).

但(dàn)究竟是(shì)什麽影響着我們的飲食習(xí)慣呢(ne)?原來(lái),一系列複雜的因素共同作用于我們的飲食攝入模式。這(zhè)些因素包括(但(dàn)不(bù)限于)我們的心理特質(及情緒狀态)、認知和感知過程、行(xíng)爲特征、心理社會(huì)(包括文化(huà))環境以及內(nèi)髒感覺體(tǐ)驗。而這(zhè)些因素又各自(zì)受到我們體(tǐ)內(nèi)不(bù)斷變化(huà)的生理、生物(wù)、神經心理和環境狀态的驅動(見(jiàn)圖1)(請參閱營養心理學研究庫)。

Figure 1. Elements of the diet-mental health relationship (DMHR) informing nutritional psychology (NP)

圖1. 飲食與心理健康關系(DMHR)的元素,爲營養心理學(NP)提供信息

Understanding the diet-mental health relationship (DMHR) involves a wealth of conceptual complexity. The burgeoning field of nutritional psychology is attempting to integrate this conceptual complexity into a singular infrastructure by which the conceptualization of the DMHR can grow (figure 1). Nutritional psychology involves understanding the myriad factors interconnecting our dietary intake with our psychological processes, functioning, and experience. A plethora of research exists (and is growing) to improve our understanding of these interconnections and is contained in the CNP Research Libraries.

理解飲食與心理健康關系(DMHR)涉及大(dà)量的概念複雜性。營養心理學這(zhè)一新興領域正試圖将這(zhè)些概念複雜性整合到一個單一的基礎設施中,以便DMHR的概念化(huà)能夠不(bù)斷發展(見(jiàn)圖1)。營養心理學涉及理解我們飲食攝入與心理過程、功能和體(tǐ)驗之間(jiān)錯綜複雜的聯系。存在大(dà)量(且不(bù)斷增長)的研究來(lái)改善我們對這(zhè)些相(xiàng)互關系的理解,這(zhè)些研究包含在CNP研究庫中。

What is Guiding What We Eat?

是(shì)什麽在引導我們的飲食?

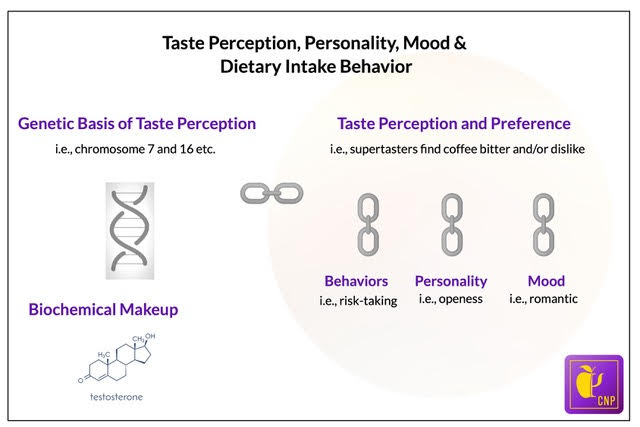

On the surface, many of us believe that what we eat is guided by what we like and want to eat (or in the current dietary intake landscape additionally, what we crave to eat and what is available to eat). In fact, what we eat goes far deeper than simply wanting and liking certain foods. A host of involuntary factors, of which we are mostly unaware, influence our daily dietary intake including our perceptions and preferences, personality, mood, behavioral attributes, and even genetics (Neuroscientist News, 2022). Let’s begin by looking at taste perception, preference, and their connection with personality traits.

從(cóng)表面上看,我們中的許多(duō)人(rén)認爲我們的飲食是(shì)由我們喜歡和想吃的食物(wù)(或在當前的飲食攝入環境中,我們渴望吃的食物(wù)以及可(kě)獲得的食物(wù))所引導的。事實上,我們的飲食遠比僅僅想要(yào)和喜歡某些食物(wù)要(yào)複雜得多(duō)。許多(duō)我們大(dà)多(duō)未意識到的非自(zì)願因素也在影響我們的日常飲食攝入,包括我們的感知和偏好、個性、情緒、行(xíng)爲特征,甚至遺傳(Neuroscientist News, 2022)。讓我們從(cóng)味覺感知、偏好及其與個性特征的聯系開(kāi)始探討(tǎo)。

Genetic Basis for Taste Perception and its Connection with Personality Traits

味覺感知的遺傳基礎及其與個性特征的聯系

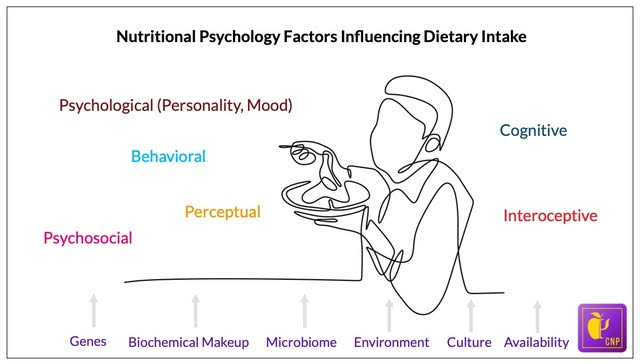

Perceiving taste involves complex pathways that interface with multiple cranial nerves and areas in our brain. The five taste sensations (bitter, sweet, umami, sour, and salt) arise because of the activation of specific taste receptor cells on the lingual papillae on the tongue. Specific genes encode the different taste receptors. Varieties in these genes lead to the expression of different proteins associated with different tasting abilities, preferences, and personality traits. This serves as the genetic basis for taste and the perception of taste.

味覺感知涉及複雜的途徑,這(zhè)些途徑與我們的多(duō)個腦神經和大(dà)腦區域相(xiàng)連。五種基本味覺(苦、甜、鮮、酸、鹹)的産生是(shì)由于舌頭味蕾上的特定味覺受體(tǐ)細胞被激活。不(bù)同的味覺受體(tǐ)由特定的基因編碼。這(zhè)些基因的不(bù)同變體(tǐ)導緻與不(bù)同味覺能力、偏好和個性特征相(xiàng)關的不(bù)同蛋白(bái)質的表達。這(zhè)構成了味覺及其感知的遺傳基礎。

Interestingly, sensory science divides people into supertasters, medium-tasters, and non-tasters. The TAS2R38 gene, located on chromosome 7, provides the genetic basis for taster status (Figure 2).

有趣的是(shì),感官科(kē)學将人(rén)們分(fēn)爲超味覺者、中味覺者和非味覺者。位于7号染色體(tǐ)上的TAS2R38基因提供了味覺者分(fēn)類的遺傳基礎(圖2)。

Supertasters are defined as individuals with uncommonly low gustatory thresholds and strong responses to moderate concentrations of taste stimuli (Supertaster – APA Dictionary of Psychology, n.d.). Supertasters have an unusually high number of taste buds. This gene in supertasters increases their perception of bitter flavors in foods.

超味覺者被定義爲具有異常低(dī)的味覺阈值和對中等濃度味覺刺激物(wù)産生強烈反應的人(rén)(“Supertaster – APA心理學詞典”,無日期)。超味覺者擁有異常多(duō)的味蕾。這(zhè)種基因變異使得超味覺者對食物(wù)中的苦味感知更爲強烈。

基因的不(bù)同變體(tǐ)導緻與不(bù)同味覺能力、偏好和個性特征相(xiàng)關的不(bù)同蛋白(bái)質的表達。

For example, supertasters tend to find the taste of coffee to be very bitter. In relation to personality characteristics, studies have found that supertasters and medium-tasters tend to be more tense, apprehensive, and imaginative than non-tasters, while non-tasters are inclined to be more relaxed, placid, and practical (Mascie-Taylor et al., 1983).

例如,超味覺者往往覺得咖啡的味道(dào)非常苦。在個性特征方面,研究發現(xiàn),超味覺者和中味覺者往往比非味覺者更加緊張、憂慮和富有想象力,而非味覺者則傾向于更加放松、平靜和務實(Mascie-Taylor等人(rén),1983)。

Science also reveals a genetic basis for sweet liking, identified by a locus on chromosome 16 (Figure 2). Researchers divide the population into three categories related to the liking for sweetness: sweet-likers, sweet-neutral, and sweet dislikers. Regarding differences in the preferences for sweetness, studies have shown that these differences predicted intentions, prosocial personalities, and behaviors (Meier et al., 2012).

科(kē)學還揭示了喜歡甜味的遺傳基礎,這(zhè)由16号染色體(tǐ)上的一個位點決定(圖2)。研究人(rén)員(yuán)根據對甜味的喜好将人(rén)群分(fēn)爲三類:喜歡甜味者、對甜味無感者和不(bù)喜歡甜味者。關于對甜味偏好的差異,研究表明,這(zhè)些差異可(kě)以預測個體(tǐ)的意圖、親社會(huì)個性和行(xíng)爲(Meier等人(rén),2012)。

Figure 2. The five taste sensations. The genetic basis for sweet liking is identified by chromosome 16, while chromosome 7 provides the genetic basis for taster status

圖2. 五種基本味覺。喜歡甜味的遺傳基礎由16号染色體(tǐ)決定,而7号染色體(tǐ)則提供了味覺者分(fēn)類的遺傳基礎

It is important to note that in addition to our genes, our biochemical makeup also plays a role in our food perception and preference. For example, one study showed that salivary testosterone levels correlated with the amount of spice (Tabasco in this case) that participants chose to add to their food (Bègue et al., 2015).

值得注意的是(shì),除了基因外(wài),我們的生化(huà)構成也在食物(wù)感知和偏好中發揮作用。例如,一項研究表明,唾液中的睾酮水(shuǐ)平與參與者選擇添加到食物(wù)中的香料量(在這(zhè)種情況下是(shì)塔巴斯科(kē)辣醬)呈正相(xiàng)關(Bègue等人(rén),2015)。

Now that we’re aware of the genetic (and biochemical) basis for taste perception and preference, and learned how our genes can influence personality, let’s look at how personality can influence food preference.

既然我們已經了解了味覺感知和偏好的遺傳(和生化(huà))基礎,并學習(xí)了基因如何影響個性,接下來(lái)讓我們看看個性如何影響食物(wù)偏好。

Personality and Food Preference

個性與食物(wù)偏好

Regarding food preferences, key factors of a person’s personality, including openness to experience (i.e., curiosity vs. caution), have been found to correlate with various aspects of food preference. For example, in a study by Conner et al. (2017), people with personality attributes like openness scored above average on preference for new food experiences. The controversy associated with such research, however, is that it has largely been conducted using self-rated food preferences, not in settings with actual food choices.

在食物(wù)偏好方面,一個人(rén)的個性的關鍵因素,包括對新體(tǐ)驗的開(kāi)放性(即好奇心與謹慎之間(jiān)的平衡),已被發現(xiàn)與食物(wù)偏好的各個方面相(xiàng)關。例如,在Conner等人(rén)(2017)的研究中,具有開(kāi)放性等個性特征的人(rén)在喜歡新食物(wù)體(tǐ)驗方面的得分(fēn)高(gāo)于平均水(shuǐ)平。然而,這(zhè)類研究的一個争議點是(shì),它們大(dà)多(duō)是(shì)通(tōng)過自(zì)我評估的食物(wù)偏好來(lái)進行(xíng)的,而不(bù)是(shì)在實際選擇食物(wù)的環境中進行(xíng)的。

個性與食物(wù)偏好的關鍵因素

Many studies have addressed this issue. For example, a 2016 study analyzed participants’ willingness to try new foods. In this study, bite-sized pieces of twelve food items were placed in front of each participant (these included: octopus, hearts of palm, seaweed, soya bean milk, blood sausage, Chinese sweet rice cake, pickled watermelon rind, raw fish, quail egg, star fruit, sheep milk cheese, and black beans). Findings showed that the most anxious participants were the least willing to try new foods (Otis, 2016). This has been supported by other publications showing that anxious patients exhibit greater food aversions (Spence, 2021).

許多(duō)研究已經探討(tǎo)了這(zhè)個問(wèn)題。例如,2016年的一項研究分(fēn)析了參與者嘗試新食物(wù)的意願。在這(zhè)項研究中,研究人(rén)員(yuán)在每個參與者面前放置了十二種食物(wù)的小(xiǎo)塊樣品(包括:章魚、棕榈芯、海藻、豆漿、血腸、中國(guó)甜年糕、腌西瓜皮、生魚片、鹌鹑蛋、楊桃、羊奶酪和黑豆)。研究結果表明,最焦慮的參與者最不(bù)願意嘗試新食物(wù)(Otis,2016)。這(zhè)一發現(xiàn)得到了其他研究的支持,這(zhè)些研究表明焦慮患者表現(xiàn)出更強的食物(wù)厭惡(Spence,2021)。

最焦慮的參與者最不(bù)願意嘗試新食物(wù)

Taste Perception and its Influence on Mood and Behavior

味覺感知及其對情緒和行(xíng)爲的影響

Now that we’ve explored some interconnections between genes, taste perception, and personality, let’s see how taste perception can influence our mood and behaviors. An example study by Vi and Obrist (2018) showed that those experiencing a sour taste were more likely engage in risk-taking. This was measured using the standardized Balloon Analogue Risk-Taking (BART) task, a computerized gambling task. Participants were asked to virtually pump up a balloon on a computer screen, with an accumulated monetary reward at stake. After each pump, the balloon either explodes or increases in size based on a randomized algorithm, yielding greater reward. Participants who had tasted something sour (as compared to a neutral water stimulus) were more likely to keep inflating the virtual balloon, risking the loss of the reward.

既然我們已經探討(tǎo)了基因、味覺感知和個性之間(jiān)的一些相(xiàng)互聯系,接下來(lái)讓我們看看味覺感知如何影響我們的情緒和行(xíng)爲。Vi和Obrist(2018)的一項研究就(jiù)是(shì)一個很(hěn)好的例子,該研究表明,體(tǐ)驗酸味的人(rén)更有可(kě)能進行(xíng)冒險行(xíng)爲。這(zhè)一結論是(shì)通(tōng)過标準化(huà)的氣球模拟風險承擔(BART)任務來(lái)衡量的,這(zhè)是(shì)一個計算機化(huà)的賭博任務。參與者被要(yào)求在計算機屏幕上虛拟地(dì)給氣球充氣,同時累積金錢(qián)獎勵。每次充氣後,氣球要(yào)麽根據随機算法爆炸,要(yào)麽增大(dà),從(cóng)而獲得更大(dà)的獎勵。與接受中性水(shuǐ)刺激的參與者相(xiàng)比,那些品嘗了酸味物(wù)質的參與者更有可(kě)能繼續給虛拟氣球充氣,從(cóng)而冒着失去獎勵的風險。

A study exploring the interrelation between taste perception and mood (Chan et al., 2013) showed that tasting something sweet made people feel temporarily more romantic. And that by having people remember an episode of romantic love, they would report some foods as being sweeter than did those who were asked to recall a jealous memory.

另一項探討(tǎo)味覺感知與情緒之間(jiān)關系的研究(Chan等人(rén),2013)表明,品嘗甜味食物(wù)會(huì)讓人(rén)暫時感覺更加浪漫。研究人(rén)員(yuán)讓參與者回憶一段浪漫的愛情經曆,這(zhè)些參與者報告說某些食物(wù)比那些被要(yào)求回憶嫉妒記憶的參與者感覺更甜。

In another study by Ren et al., (2014), researchers exposed a group of participants to the sweet taste of Oreo cookies. This exposure resulted in a greater interest in initiating relationships with a potential partner.

Ren等人(rén)(2014)的另一項研究則揭示了甜味對人(rén)際關系的影響。研究人(rén)員(yuán)讓一組參與者品嘗奧利奧餅幹的甜味。這(zhè)種甜味體(tǐ)驗導緻參與者對與潛在伴侶建立關系的興趣增加。

A study by Greimel et al., (2006) found that prompting people to remember being mistreated at work resulted in bitter tastes being rated as more intense, while watching a joyful film clip (compared to a sad movie clip) resulted in participants rating a sweet drink as more pleasant.

Greimel等人(rén)(2006)的研究揭示了情緒狀态對味覺感知的顯著影響。該研究發現(xiàn),當引導人(rén)們回憶在工(gōng)作中受到的不(bù)公待遇時,他們會(huì)對苦味食物(wù)的感知更爲強烈,認爲其味道(dào)更加苦澀。相(xiàng)反,當參與者觀看一段令人(rén)愉悅的電(diàn)影片段(與觀看悲傷電(diàn)影片段相(xiàng)比)時,他們會(huì)更傾向于将甜飲料評價爲更加美味。

Taste Perception and Clinical Disorders

味覺感知與臨床疾病

Some research on taste perception in the context of mental health shows that depressed patients have differences in perception of taste. While some studies have reported no difference in taste perception in depressed patients (Arrando, 2015; Nagai, et al., 2015), researchers Hur et al. (2018) found that the prevalence of altered smell and taste among patients with major depressive disorder was 39.8% and 23.7% respectively.

在心理健康的背景下,對味覺感知的研究表明,抑郁症患者存在味覺感知上的差異。盡管一些研究(如Arrando, 2015; Nagai等人(rén), 2015)報告了抑郁症患者與正常人(rén)在味覺感知上沒有顯著差異,但(dàn)Hur等人(rén)(2018)的研究發現(xiàn),在患有重度抑郁症的患者中,嗅覺和味覺改變的發生率分(fēn)别爲39.8%和23.7%。

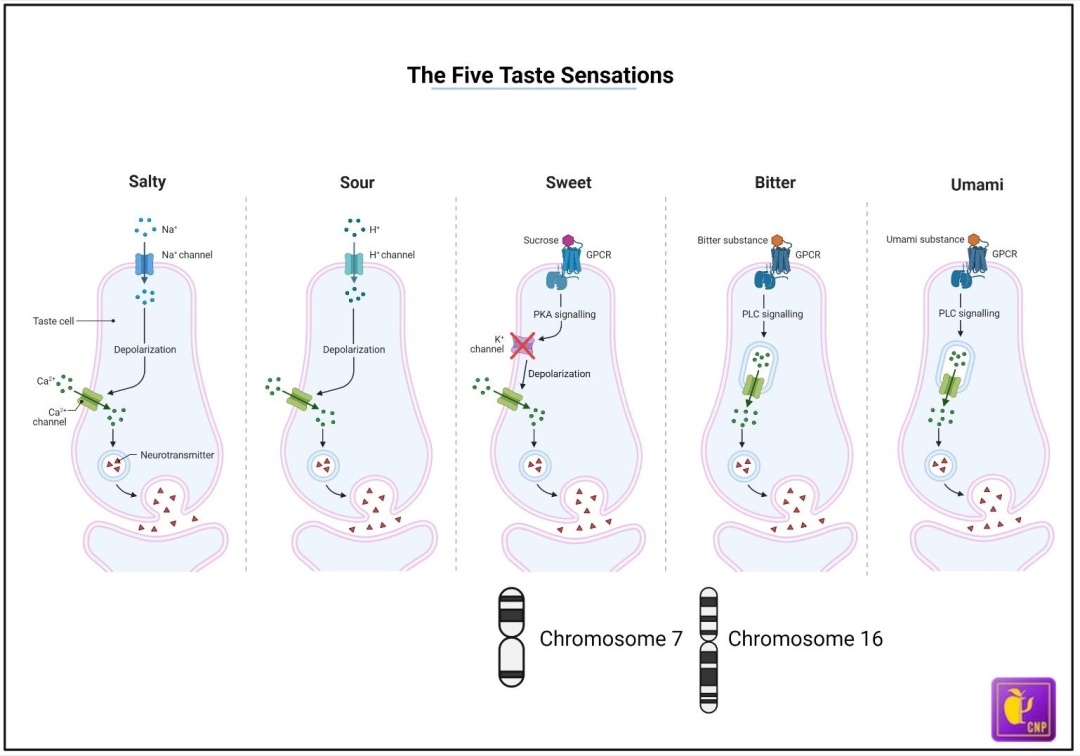

These changes in taste perception are hypothesized to be due to several mechanisms, but one mechanism seems to involve neurochemical changes that happen in our brain due to either emotional or pathological processes (e.g., depression leads to elevation of inflammatory cytokines like interleukin 6). These changes can result in actual changes in the gustatory system.

這(zhè)些味覺感知的變化(huà)被認爲是(shì)由多(duō)種機制(zhì)引起的,其中一個重要(yào)機制(zhì)涉及大(dà)腦中由于情感或病理過程(如抑郁症導緻的炎症細胞因子如白(bái)介素6水(shuǐ)平升高(gāo))而發生的神經化(huà)學變化(huà)。這(zhè)些變化(huà)可(kě)能會(huì)導緻味覺系統的實際改變。

It is hypothesized that changed taste thresholds could be attributed to reduced serotonin and noradrenaline levels in depressed patients, as suggested by Heath et al. (2006) (Figure 3). This proposed mechanism was supported by another study (Kim et al., 2017), which found reduced expression of 5‐HT1A receptors for serotonin in the taste cells of rats that developed anhedonia — a common symptom of depression. Case reports demonstrate that a change in taste is a neglected symptom in depressed patients that is worthy of further investigation (Miller & Naylor, 1989; Mizoguchi et al., 2012).

Heath等人(rén)(2006)提出的假設認爲,抑郁症患者味覺阈值的變化(huà)可(kě)能與血清素(5-羟色胺)和去甲腎上腺素水(shuǐ)平的降低(dī)有關(如圖3所示)。這(zhè)一機制(zhì)得到了Kim等人(rén)(2017)的研究支持,他們發現(xiàn),在出現(xiàn)快(kuài)感缺失(抑郁症的一個常見(jiàn)症狀)的大(dà)鼠中,其味覺細胞中的5-HT1A血清素受體(tǐ)表達減少。此外(wài),病例報告也表明,味覺改變是(shì)抑郁症患者中被忽視(shì)的一個症狀,值得進一步深入研究(Miller & Naylor, 1989; Mizoguchi等人(rén), 2012)。

Figure 3. Human gustatory pathway. Variations in serotonin levels are associated with different thresholds for certain tastes like bitter and sweet (Heath, 2006).

圖3. 人(rén)類味覺通(tōng)路(lù)。血清素水(shuǐ)平的變化(huà)與某些味覺(如苦和甜)的阈值變化(huà)相(xiàng)關聯(Heath, 2006)。

Research also shows that patients with panic disorders can have exhibited reduced sensitivity to bitterness (DeMet et al., 1989), while anxiety levels are positively correlated with the taste thresholds for bitterness and saltiness (Heath et al., 2006).

研究還表明,驚恐障礙患者對苦味的敏感性可(kě)能會(huì)降低(dī)(DeMet et al., 1989),而焦慮水(shuǐ)平與苦味和鹹味的味覺阈值呈正相(xiàng)關(Heath et al., 2006)。

According to Hur et al. (2018), it may be advisable for primary care providers to screen their patients for depression or other psychiatric conditions when they report changes in taste or smell.

根據Hur等人(rén)(2018)的研究,當患者報告味覺或嗅覺發生變化(huà)時,建議初級保健提供者篩查患者是(shì)否患有抑郁症或其他精神疾病。

Conclusion

結論

In this article, we’ve had a little ‘taste’ of how our genes influence our taste perception and preferences. The DMHR plot thickens when we begin to be aware of how these perceptions and preferences can interplay with our personality, mood, and behaviors (figure 4).

在這(zhè)篇文章中,我們對基因如何影響我們的味覺和偏好有了一點“了解”。當我們開(kāi)始意識到這(zhè)些感知和偏好如何與我們的個性、情緒和行(xíng)爲相(xiàng)互作用時,DMHR的情節就(jiù)會(huì)變得更加複雜(圖4)。

Figure 4. Interconnections between genes, taste perception, and preference, behaviors, personality, and mood.

圖4. 基因、味覺感知與偏好、行(xíng)爲、個性與情緒之間(jiān)的相(xiàng)互聯系

For example, we learned how anxious individuals can prefer a narrower range of food while people with personality attributes like openness typically score above average on preferences for new food experiences. Intriguingly, differences in food behavior and taste perception have been linked with circulating levels of certain neurotransmitters like serotonin and can affect taste perception in clinical disorders.

例如,我們了解到焦慮的個體(tǐ)往往偏好更爲有限的食物(wù)種類,而那些具有開(kāi)放性等個性特征的人(rén)則在新食物(wù)體(tǐ)驗的偏好上通(tōng)常得分(fēn)高(gāo)于平均水(shuǐ)平。這(zhè)揭示了個性特征對食物(wù)選擇的重要(yào)影響。更有趣的是(shì),食物(wù)行(xíng)爲和味覺感知的差異與體(tǐ)內(nèi)某些神經遞質(如血清素)的循環水(shuǐ)平密切相(xiàng)關,這(zhè)些差異在臨床疾病中也可(kě)能對味覺感知産生影響。

While not lending to a conclusive understanding of the factors involved in dietary intake, our goal with this article is to provide you with a new awareness of the interconnection that occurs between your genes, personality, emotions, and food-related behaviors and preferences.

盡管本文未能爲飲食攝入所涉及的因素提供全面而确定的解釋,但(dàn)我們的目标是(shì)通(tōng)過這(zhè)篇文章,讓您對基因、個性、情緒以及與食物(wù)相(xiàng)關的行(xíng)爲和偏好之間(jiān)錯綜複雜的相(xiàng)互聯系産生新的認識。

To learn more,

進一步學習(xí)

visit the CNP Diet and Personality and Diet and Sensory-Perception research categories in the NPRL.

訪問(wèn)NPRL中的CNP飲食與個性及飲食與感官感知研究分(fēn)類

References

Arrondo, G., Murray, G. K., Hill, E., Szalma, B., Yathiraj, K., Denman, C., & Dudas, R. B. (2015). Hedonic and disgust taste perception in borderline personality disorder and depression. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science, 207(1), 79–80. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.150433

Bègue, L., Bricout, V., Boudesseul, J., Shankland, R., & Duke, A. A. (2015). Some like it hot: Testosterone predicts laboratory eating behavior of spicy food. Physiology & Behavior, 139, 375–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSBEH.2014.11.061

Chan, K. Q., Tong, E. M. W., Tan, D. H., & Koh, A. H. Q. (2013). What do love and jealousy taste like? Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 13(6), 1142–1149. https://doi.org/10.1037/A0033758

Conner, T. S., Thompson, L. M., Knight, R. L., Flett, J. A. M., Richardson, A. C., & Brookie, K. L. (2017). The role of personality traits in young adult fruit and vegetable consumption. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(FEB). https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYG.2017.00119

DeMet, E., Stein, M. K., Tran, C., Chicz-DeMet, A., Sangdahl, C., & Nelson, J. (1989). Caffeine taste test for panic disorder: Adenosine receptor supersensitivity. Psychiatry Research, 30(3), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90014-0

Greimel, E., Macht, M., Krumhuber, E., & Ellgring, H. (2006). Facial and affective reactions to tastes and their modulation by sadness and joy. Physiology & Behavior, 89(2), 261–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSBEH.2006.06.002

Heath, T. P., Melichar, J. K., Nutt, D. J., & Donaldson, L. F. (2006). Human taste thresholds are modulated by serotonin and noradrenaline. The Journal of Neuroscience, 26(49), 12664–12671. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3459-06.2006

Hur, K., Choi, J. S., Zheng, M., Shen, J., & Wrobel, B. (2018). Association of alterations in smell and taste with depression in older adults. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology, 3(2), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1002/LIO2.142

Kim, D., Chung, S., Lee, S. H., Koo, J. H., Lee, J. H., & Jahng, J. W. (2017). Decreased expression of 5-HT1A in the circumvallate taste cells in an animal model of depression. Archives of Oral Biology, 76, 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ARCHORALBIO.2017.01.005

Mascie-Taylor, C. G. N., McManus, I. C., MacLarnon, A. M., & Lanigan, P. M. (1983). The association between phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) tasting ability and psychometric variables. Behavior Genetics, 13(2), 191–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01065667

Meier, B. P., Moeller, S. K., Riemer-Peltz, M., & Robinson, M. D. (2012). Sweet taste preferences and experiences predict prosocial inferences, personalities, and behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(1), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1037/A0025253

Mizoguchi, Y., Monji, A., & Yamada, S. (2012). Dysgeusia successfully treated with sertraline. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 24(2). https://doi.org/10.1176/APPI.NEUROPSYCH.11040095

Nagai, M., Matsumoto, S., Endo, J., Sakamoto, R., & Wada, M. (2015). Sweet taste threshold for sucrose inversely

Neuroscientist News. (2022, June 14). Do our genes determine what we eat? https://neurosciencenews.com/genetics-taste-perception-20833/

correlates with depression symptoms in female college students in the luteal phase. Physiology & behavior, 141, 92–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.01.003

Otis, L. P. (1984). Factors influencing the willingness to taste unusual foods. Psychological Reports, 54, 739–745.

Ren, D., Tan, K., Arriaga, X. B., & Chan, K. Q. (2014). Sweet love: The effects of sweet taste experience on romantic perceptions. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1177/0265407514554512, 32(7), 905–921. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407514554512

Smith, W., Powell, E. K., & Ross, S. (1955). Manifest anxiety and food aversions. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 50(1), 101–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/H0049253

Supertaster – APA dictionary of psychology. (n.d.). Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://dictionary.apa.org/supertaster

Spence C. (2021). What is the link between personality and food behavior?. Current research in food science, 5, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2021.12.001

Vi, C. T., & Obrist, M. (2018). Sour promotes risk-taking: An investigation into the effect of taste on risk-taking behaviour in humans. Scientific Reports, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-018-26164-3